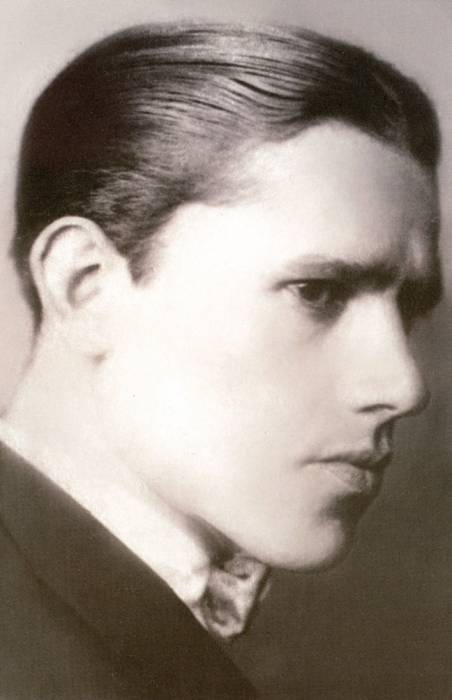

Oliverio Martínez

1901-1938

“It could be said that his fate had been clearly drawn: to come, to produce his art and leave, all very quickly. He had no time for more, not even to enjoy his work, to feel his success. His arrival was strange, he belonged to that type of artist working alone at home, almost hiding, without contacts, one of those who in all quietness and through an unavoidable self-discipline produced a wonderful ouevre” (words by architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia, responsible for the construction of the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City).

Oliverio was the second child of what would become a large family in (he had 15 siblings, out of which 12 reached adulthood and a thirteenth was adopted). His parents were Elena de Hoyos de la Garza, a strict catholic and Néstor Martínez Perales, a liberal, accountant in a rail company.

In 1907 the family moved to Mexico City, where Oliverio went to school and showed great talent for mathematics, algebra and geometry. He attended college in Mexico City between 1914 and 1919. He had been a good student and an obedient son, until he abandoned his studies in medicine and his mother warned him she “would not tolerate loafers” at home.

Oliverio then moved to New York City to work with his maternal uncles in the offices of the Mexican Railroad. Living conditions were unhealthy: two of Oliverio’s flatmates came down with TB and it is likely that Oliverio himself was infected then also. His health was so poor he resolved to return to Mexico City and to move in with the family. From there, and in order to improve his health, he was sent out to work with other uncles in a lumber yard in the mountains of Durango, in the north of México.

Oliverio was always an affectionate and protecting brother, a model to some of his younger siblings. Some of them moved to Texas, where they stayed for 4 years. During those years they would correspond with Oliverio and tell him about their experiences. Oliverio wrote back loving letters in his small beautiful handwriting, always encouraging the younger ones to follow their interests freely, and was enthusiastic about their respectful and loving replies. He thus wrote to Enrico, encouraging him to define his calling and expressing his certainty that he would become “one of the best persons I have known”.

To Ricardo, who was already a skilled draftsman and 17 years his junior, he would write constantly and exchange with him comic drawings, while at the same time encouraging him to “work more and eat less sweets”.

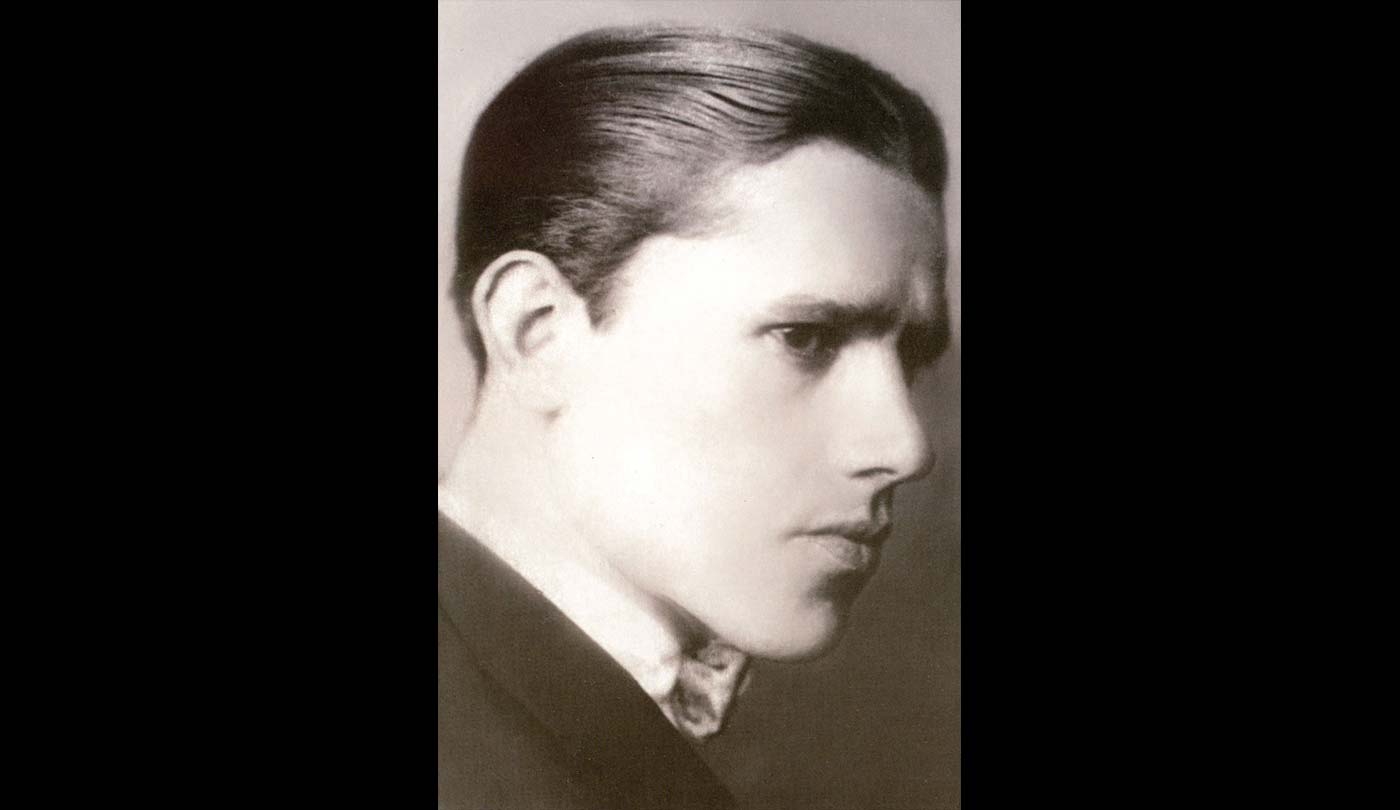

In 1929 Oliverio met and fell in love with his nieghbour, Eloína Peláez, 14 years his junior. He was so much in love that they got married a few years later, against her parents’ wishes. They had a daughter, María Elena. There remain many letters to Eloína, in which he tells her about his vocation and how he cannot stop thinking about her: “My name is Oliverio Guillermo Martínez. I come from Piedras Negras, Coahuila and I am 27 years old. I am a fervent sculptor. But when I think of you I cannot bear to be spoken to.”

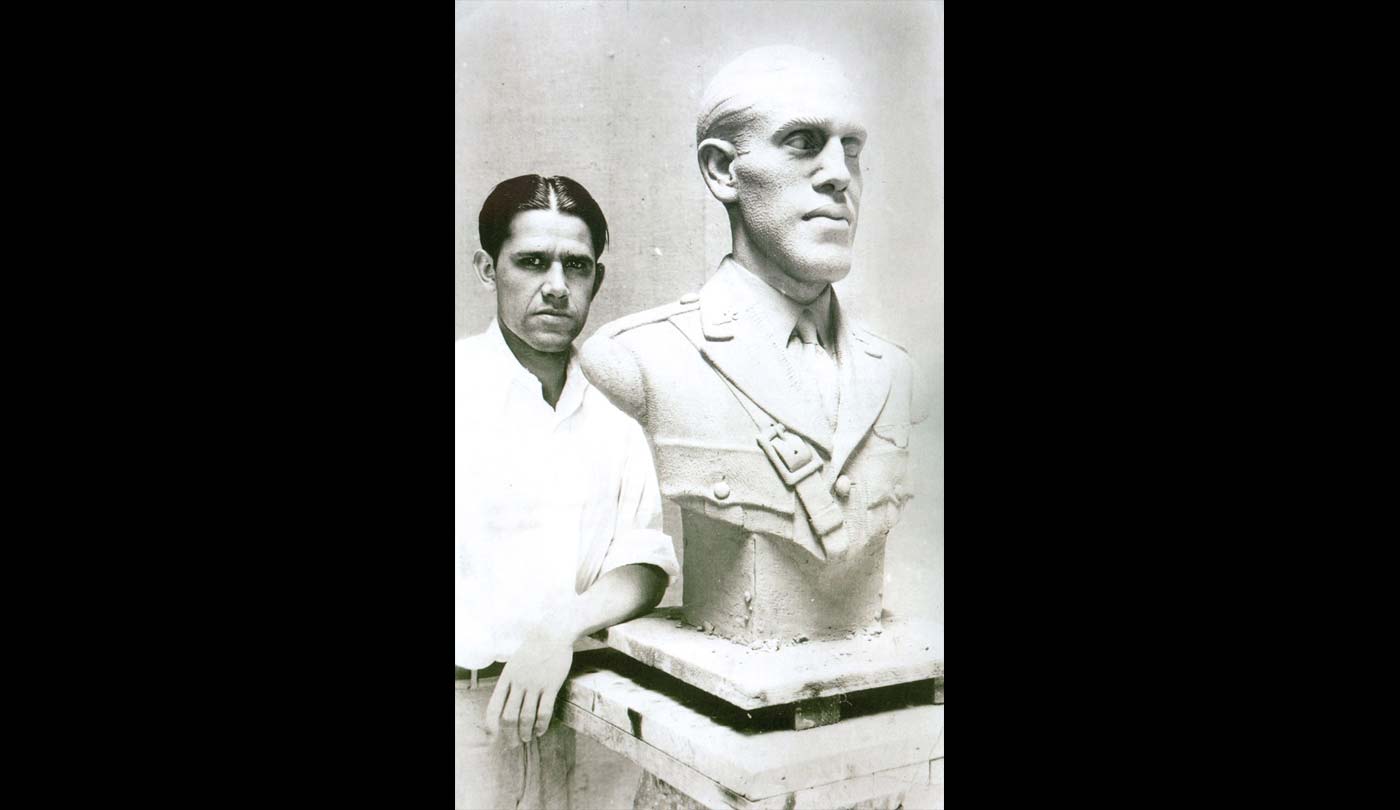

Oliverio’s first serious encounter with art took place when he was already 27 and was admitted at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts. At the end of his first year he was awarded the first price in a sculpture contest and his work was exhibited in the Academy’s courtyard. Shortly after, he made a sculpture of Emilio Carranza, which is now in Saltillo, and a monument commemorating Emiliano Zapata, which is in Cuautla. He worked in an atelier until 1934, when he took part as a contender in the competition to build groups of sculptures which would crown the monument to the Revolution, in Mexico City.

Oliverio did not theorize about art, he produced it. He was independent and free of influences, always trying to figure out for himself the secrets of volume and to use his enormous creative energy. Although he had been a pupil of José María Fernández Urbina, he was regarded as self-taught, since his formal education was incomplete. He took part in founding what some critics call the Mexican School of Sculpture.

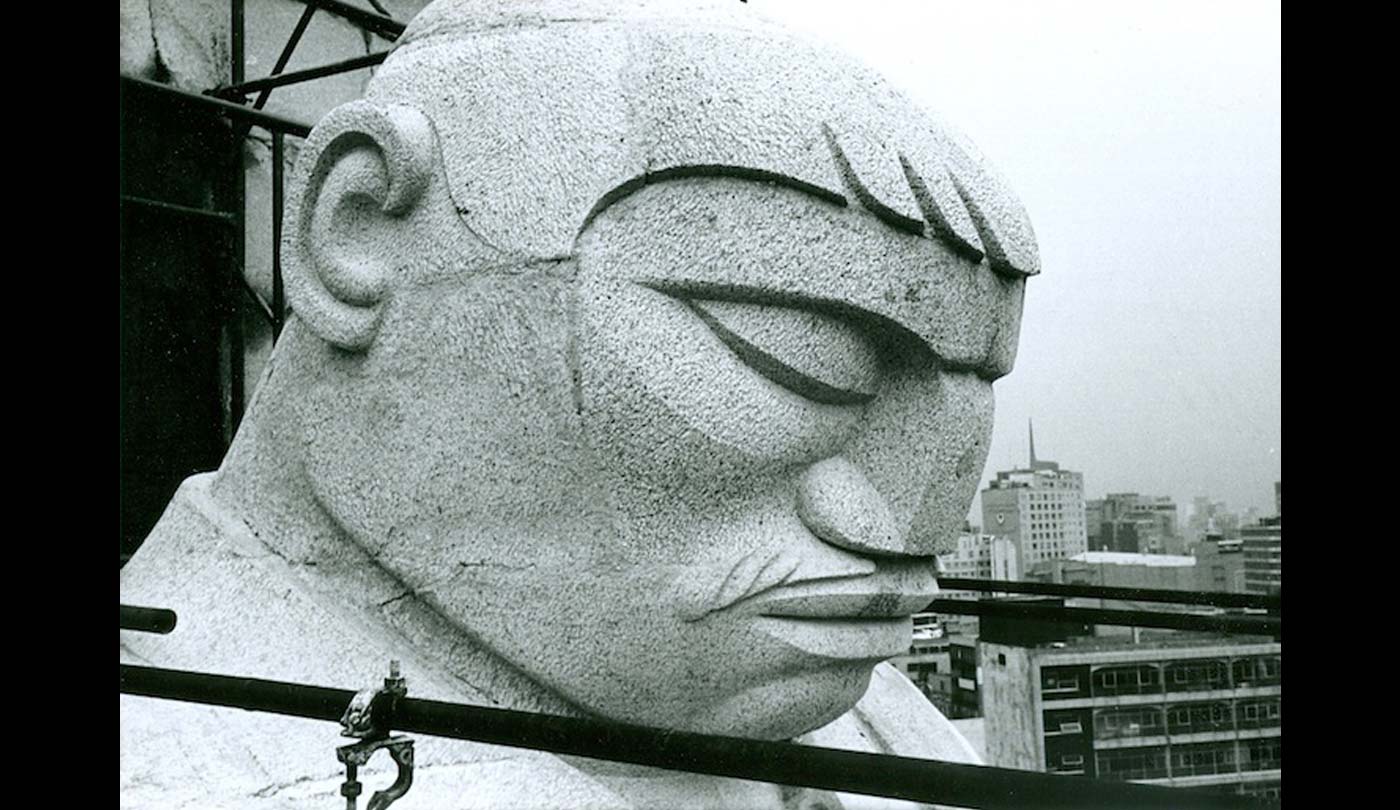

Oliverio’s work has been described as a fortunate mixture of dynamism, strength and extreme grandiosity, even though most of his works are in a small format. It expresses the artistic heritage of Prehispanic Mexico, and yet boasts modernistic features, such as the representation of themes related to social justice, based on the tenets of the Mexican Revolution. These, together with the mural paintings of the time, brought art and the people into close contact.

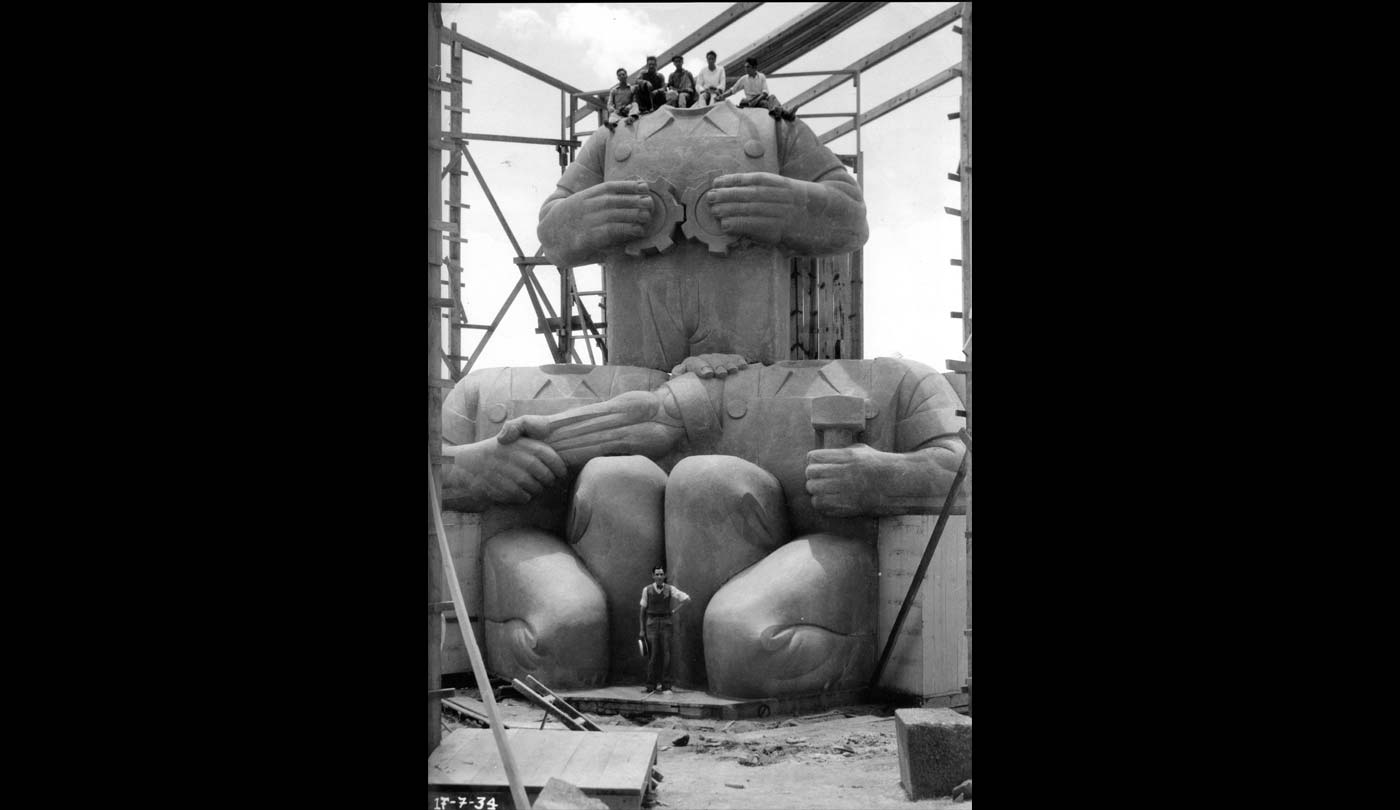

Oliverio’s career lasted only about 10 years. He was awarded the contract for the sculptures for the Monutment to the Revolution among 40 competitors. The call for applications specified that “The monument is to glorify the people and will be dedicated to the Revolution of yesterday, today, tomorrow and always.”

Obregón Santacilia said “…for me Oliverio Martinez was a complete stranger. We actually had to look for him in order to inform him that he had been chosen in the first round of the competiton, together with Federico Canessi and Fernando Leal among others, and that he had to develop the first draft and take part in the second round. He was one of the chosen to produce his sketch in its actual size. By the third round his triumph was a fact. The simplicity of his composition was the main feature, but what made him succeed was his understanding of the architectural aspect of the monument, in such a way that it is difficult to tell where the building ends and the sculptures begin”.

Obregón Santacilia added: “…in spite of the beauty of his project, some critics were negative even before having seen it and tried to hinder its construction. Nevertheless Oliverio can be at peace, since from now on criticism shall be positive. The people have felt the monument, regard it as their own and find their own image represented in the sculptures. “ Oliverio’s models were the stone masons, the foremen, their wives and children.

It is remarkable to perceive Oliverio’s strong presence and long lasting influence in the world of sculpture, taking into account that his professional life was so brief, and to confirm that he has become a beacon in the Mexican sculptoric environment. A faint but constant beacon, a guide to future generations. Oliverio’s work is regarded as a catalyst in Mexican sculpture of the XXth century and, in spite of his short artistic career, a bridge between the XIXth and XXth centuries.

The works at the Monument were temporarily suspended in December 1934, due to the change of government, and resumed six months later, to be concluded in 1938. Oliverio’s health worsened during that time. He had support from close friends such as Federico Canessi and Francisco Zúñiga, but was talked into separating from his wife and daughter by his parents in law, a sacrifice that affected his phyisical health and damaged him emotionally. This, as well as not being able to join the stone masons on the monument, plus the harsh criticism against his sculptures, and finally his poverty, hastened his death.

Arteaga, Agustín y Tibol, Raquel. Fuerza y volumen. El lenguaje escultórico de Oliverio Martínez. México: Museo Nacional de Arte, 1996.

Guzmán Urbiola, Xavier. Oliverio Martínez, 1901-1938. México: Museo Nacional de Arte, Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila, 2012.