PORTRAITS IN THE WORK OF RICARDO MARTÍNEZ

October 2021

Aurora Avilés García

Zarina Martínez

The portrait genre, which we intend to explore through this essay, is a subject of interest within the vast production by Ricardo Martínez.

What is a portrait? The most traditional definition of this art genre is that it is an effigy, that is to say, a faithful image of a person presented through different techniques and artistic materials. However, in one of the most emblematic works on the subject, theoreticians Galienne and Pierre Francastel, (1) warn that there was a reformulating of the genre based on avant-garde experiences, such as impressionism, cubism, fauvism and abstract art, among others. The different concepts and experiments performed in this revolutionary art context resulted in a wider and newer notion of the genre, which went, from being a faithful image of a person, to the recreation of some of the subject’s physical features or “signs” as perceived by another human being, in this case the artist. Thus, the image of the person portrayed is based on the other’s vision, which is subjective, and is therefore a reconstructed image. Throughout the development of modern and contemporary painting, the definition of portrait has been reformed, transformed and adapted. In a portrait one knows and recognises the subject. (2) The role of the spectator is essential, since his or her subjective perception intervenes in the re-creation of the work, in the same way as the artist’s in its initial creation. In a portrait a series of processes come together, such as the artist’s subjectivity, his or her vision of the subject and his or her artistic ideas, as well as the recognition of the image and its re-creation in the spectator’s eyes.

Ricardo Martínez's work in the field of figurative painting is well known; during his first creative period he covered a great variety of subjects, such as landscapes, popular culture images and characters, mothers and fathers with their children, just to mention a few, before he chose to represent the human figure, something he developed until the end of his life. The portraits registered to date were performed during the first period of his work, between the forties and fifties of the 20th Century. The Ricardo Martínez Foundation has registered 16 portraits and has knowledge of a seventeenth, which has unfortunately been impossible to trace.

(1) Galienne y Pierre Francastel, El retrato (España: Ediciones Cátedra, 1978) 9.

(2) Francastel, El retrato, 10.

The techniques are different: four of them are in pencil on paper, four in sanguine or red chalk on paper and nine in oil on canvas. (3)

A careful look at these works allows us to perceive some of the main features of the artist's work in the first period of his production: his knowledge of the painting tradition, the observation of the works by contemporary artists and the inclusion and re-interpretation of some of their features in his own creation. (4) Martine'z portraits display a thorough knowledge of the traditional media of the genre, which is evident in the use of a neutral background or a landscape, as well as in the use of front facing or three-quarter view. These tools blend with the influence of artists belong to the Contemporáneos literary and artistic group like Julio Castellanos, Manuel Rodríguez Lozano and other avant-garde artists, such as Giorgio de Chirico (Italian artist born in Greece, 1888-1978), whose works were admired and spread by the group. It is well known that Martínez was an admirer of De Chirico and was well acquainted with the production of the members of Contemporáneos.

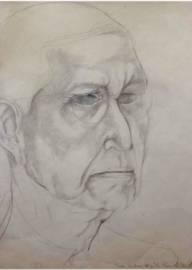

The elements mentioned above can be observed in the portraits Ricardo Martínez made both of his wife Zarina Lacy (figs. 2 y 3) and of his parents, whom he portrayed on several occasions. (5) (figs. 4 y 5) Among these is the diptych under the title “Double portrait” (1942) (fig. 6), in which he portrayed his parents, each one of them holding something which defines them: Néstor Martínez is holding music notes and Elena de Hoyos a Bible. The traditional elements of the genre are evident in this piece, with the subjects in front of a landscape that serves as background. The representation of landscapes in portraits became popular in the 15th Century in places such as Ferrara, Venice and Florence, the latter where portrait painting achieved its highest originality around 1480. (6) The idea behind this was that a person was not complete if deprived of the elements that formed his or her everyday life, and landscape proved to be a natural framework within which the subject moved and performed everyday activities. The landscape in the diptych is interesting because it appears in other works of the same period, so it is likely that it represents places known by the artist and his family. In this way the artist not only provided further information about his subjects through the objects in their hands, but also a context to their everyday activities. The father’s eyes are black and almond shaped in the style of Julio Castellanos (1905-1947), who used to paint his subjects with such features. In this piece we can observe the combination of the plastic experiments of the author with elements he observed in other artists and his subjective perception of persons close to him. The subjects are presented by the artist as he perceives them, their physical features and those attributes that define them (the notes and Bible) relate eloquently with the pictorial resources, and one artistic element in this early period, which he will develop later, is already apparent: the creation of volume through the use of light.

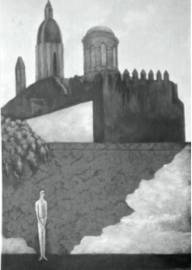

Two individual portraits of the artist’s parents, “In memory of my father” (1944) (fig. 7) and “Portrait of my mother” (1945) (fig. 8), seem to sustain a dialogue: the former is a posthumous tribute to Néstor Martínez, while in the latter, Elena de Hoyos is portrayed most likely in widow’s weeds. The former is an example of the knowledge Ricardo Martínez had of the work of Manuel Rodríguez Lozano (1896-1971), whose influence is clear in the elongated, female figures clad in tunic-like rebozos, which appear in the second and third levels of the composition. Rodríguez Lozano often represented such figures in his work from 1940. The portrait displays a deep knowledge of the plastic language of Giorgio de Chirico who, as mentioned earlier, was an important influence in the works of Ricardo Martínez. De Chirico was the founder of metaphysical painting, whose main features are solitary, melancholy and enigmatic spaces with deep shadows and different vanishing points, where the architectural proportions are larger in relation with the human figure. All these features can be perceived in the background of the portrait.

(3) Besides the portraits discussed in this essay, there are portraits of two friends: one of Aurora Flores de Díez-Canedo and the other of photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo. There is another portrait in oil on canvas, of which there are no details other than its title, “Portrait of Mr. Gilmour”.

(4) Vid. Aurora Avilés García, “1940-1989. De la búsqueda a la consolidación de un estilo” (From the quest for to the definition of a style), in Ricardo Martínez, a 100 años de su nacimiento (México: Fundación Ricardo Martínez, Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes, 2018), 40-53.

(5) There are other portraits of Martínez’s parents in pencil and three of Zarina Lacy, one in sanguine and the others in oil on canvas.

(6) Francastel, El retrato, 103.

“In memory of my father” was shown for the first time in the second solo exhibition of Ricardo Martínez at the Gallery of Mexican Art in 1945, where the artist presented a number of works which displayed his knowledge of De Chirico’s style as well as his own interpretation of it. Another portrait displayed in this exhibition was “Portrait of Zarina” (1945) (fig. 9), based on the traditional elements of the genre, such as natural surroundings as background and an architectural component which defines it, as well as the traditional pose of the subject. Moreover, the portrait reminds the viewer of the self-portraits of De Chirico during the period where he went “back to normal” towards the end of his career, with heavily clouded skies and well-defined architectural features in the background. For De Chirico these works expressed some of his most constant concerns: “the encounter of sky and architecture as a metaphor of the clash between nature and culture”. (7) This statement seems to apply to “Portrait of Zarina”.

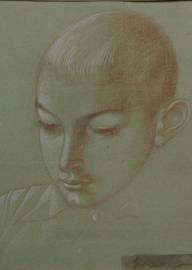

During the fifties Ricardo Martínez made some portraits of children. Among them are two made in sanguine (the sketch for the oil portrait of Bernardo Giner [fig. 10], and one of his eldest son Ricardo [fig. 11]) and three in oil on canvas. One of the them, “Portrait of Bernardo” (1950) (fig. 12), is emblematic in the context of the artist’s work. Both this and the portrait of José Luis Martínez (1952) (fig. 13) were displayed in the retrospective exhibition of Ricardo Martínez at the Museum of Mexico City in 2011, while the sketch of “Portrait of Bernardo” (fig. 10) was exhibited in the Centenary exhibition “Ricardo Martínez. Desde el interior”, which took place at the Museum of the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City in 2018.

The Ricardo Martínez Foundation is aware that the artist made a sanguine portrait of his nephew Juan Moch, of which unfortunately there is no information as to its whereabouts. Based on the dates of the other portraits, and on the basis of the likely age of the subject at the time, it can presumed that the portrait was made at the end of the forties or at the beginning of the fifties.

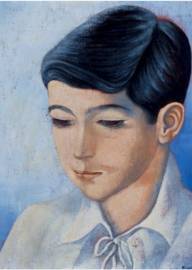

The three oil portraits –“Portrait of Bernardo”, “Portrait of José Luis Martínez” and “Portrait of Marina Urquidi” (1955) (fig. 14)–, display a deep knowledge of the traditional elements of the genre and a masterly use of them by the artist. The subjects are presented in a three-quarter pose with a neutral background. In the two first the background is blue, (8) a primary colour and a recurring element in other genres throughout Martinez’s production. These plastic tools became popular in Europe during the second half of the 15th Century, through exchanges between Flanders and Florence. A new type of portrait, in which the subject “was presented with a neutral background in a three-quarter pose or in profile, never facing the front, cut just below the shoulders (…), the face is lifelike, without too many details, but presenting instead different levels in which there is a skilful use of colour,” (9) emerged at that time, and would become an international trend.

In these works, the technical resources are well blended with the artist’s subjectivity and his perception of his object. Even though all three paintings were commissioned, there is a personal, affective element in all of them. Bernardo, José Luis and Marina were children of close friends, both of Ricardo Martínez and of one another: Francisco Giner de los Ríos, José Luis Martínez and Víctor Urquidi. It is unlikely that the artist made any more portraits after 1955, with the exception of pencil caricatures he used to make of members of his family at intimate moments.

(7) María Teresa Méndez Baiges, Modernidad y tradición en el trabajo de Giorgio de Chirico (Modernity and tradition in the work of Giorgio de Chirico) (México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2001) 245.

(8) It is interesting to observe that the background in Marina Urquidi’s portrait is mainly pink.

(9) Francastel, op. cit., 97.

The oil “Portrait of Bernardo”, as well as its sketch in sanguine, were made in 1950. The Giner de los Ríos family lived in San Ángel when Ricardo Martínez portrayed Bernardo, who would be 10 years old at the time. Francisco, Bernardo’s brother, tells that, in spite of the age difference, Ricardo Martínez and Bernardo became good friends and would play soccer in the ravine which is now Leon Felipe street. The Giner family left for Chile when Francisco started working for CEPAL in Santiago in 1953 and took both the sketch and the painting with them. They brought them back to Mexico in 1963, back to Santiago in 1966, later to Spain in 1975 and back to Mexico in 2010. Bernardo died in 1999.

Of his portrait, José Luis Martínez recalls: “Ricardo portrayed me, I think it was in 1952. My father used to take me to the house in Etna street every Sunday. I got bored to death, but had patience. In the end the suffering was worth it.” José Luis Martínez became a diplomat and is now Mexico’s Ambassador in Turkey.

About her own portrait, Marina tells: “I remember the process very well. Ricardo was very sweet to me. I was only 6 years old and the painting was to be a gift from my father to my mother. When I saw it completed I was indignant: ‘I do not look like that at all and my cardigan was not white!’ In time I realised that, in his interpretation, Ricardo had captured the essence of who I was and would go on being and that, as years went by, resembled me more and more. This can also be appreciated when the portrait is compared to a photograph of myself at 52, another ‘interpretation’… Ricardo’s work is fantastic! I cannot appreciate enough having been one of his models!’”

The value of these three paintings lies also in the subjectivity of the person portrayed and in his or her own vision of himself or herself represented on the canvas: he or she recognises himself or herself. Thus, the portraits by Ricardo Martínez go through a number of processes, such as the knowledge and use of traditional painting resources, the elaboration of his own proposals based on the influence of contemporary artists, his perception of his subject and the subject’s perception of his or her own image as produced by the painter. All these elements come together in a powerful way in the artist’s work and reveal an aspect of his art as a portrait painter that allows us to appreciate his work from a wider perspective.